Occupy Wall Street: The Day After

I’m not a spokesperson for Occupy Wall Street; they don’t have a spokesperson and don’t want one. I’m not sure I can even claim to be one of them. As a New Yorker, I had the luxury of sleeping in my own apartment instead of on the unergonomic granite slabs of Zuccotti Park and subsisting on bean sprouts and chickpeas for weeks. But I visited OWS often, and provided material support in the form of cheeseburgers, umbrellas, hot chocolate and comics, and occasionally volunteered at the “People’s Library” there, where I used my position to surreptitiously weed Tom Robbins and Dune out of the “Classics” bin. The thing that upset me most viscerally in reading about the police raid on OWS was learning that all those books--thousands of them, including two of my own--had been thrown out. The library’s laptops were smashed, their archive lost. (I’m told about 10% of the books have since been recovered.) Well, there is a fine old historical tradition of official book-destruction of which the NYPD can now claim to be a part. They are in elite company.

I didn’t always enjoy being at Occupy Wall Street. It was claustrophobic, crowded, and loud. The drumming was insufferable. Large numbers of people shouting the same thing in unison always gives me the willies, regardless of what they’re shouting. I don’t have much patience for dogmatic anarchists, that inevitable contingent for whom legalizing hemp is the most urgent issue on the national agenda, or people whose tattoos are appropriated from cultures their own ancestors eradicated. I saw some people whose mental illness was mistaken, by the impressionable young, for political conviction. There was the guy whose sign accused Senator Barney Frank of raping children, and the guy with the ZIONISTS CONTROL WALL ST sign, who was, cheeringly, ceaselessly harried by an unshakable tormentor with a sign that said ASSHOLE with an arrow he had to scurry to keep continually pointed at its target.

But once you got past the conspicuous fringe of creeps and dingbats, you found a dedicated core of people who were intelligent and conscientious and decent. I met and befriended people like Noah, a twenty-year-old who’d been planning on going backpacking in Hawaii and came to Zucotti Park instead, a talented photographer who took a picture of me I’ll be using as the publicity shot for my next book. And Joey, a machinist from Cincinnati—the kind of guy who would’ve been set for life with a factory job a generation ago—who’d been reduced to washing dishes in the same bar where he used to drink after work. At OWS he manned the “Free Empathy” booth, effectively acting as a counselor, and also served on the internal security patrol. In an ideal world-- the kind OWS was trying to jerry-rig--Joey would be a small-town sheriff, the guy everyone both likes and respects. If he asked someone to keep the noise down because people were trying to sleep, they’d actually comply, because it was Joey.

Even my friends there complained that they were so continually harried and distracted by the kinds of intramural conflicts that arise in any group of human beings living together—the new medical tent encroaching on their living space, the inevitable picayune martinets, the drummers’ need to drum ceaslessly vs. the homo sapiens’ need for sleep—that it was hard to focus on their ultimate purpose in being there. But as overwhelming and irritating as it could be, I liked going there, for the same reason I like going to libraries, concerts, or church: it was a place where large numbers of people were gathered to devote themselves to an enterprise other than the pursuit of money. It is exhilarating to inhale the air of conviction, of belief, instead of the usual sour smell of self-interest, like an Indian Summer day in November.

More importantly, leaving aside the dreadlocks and noserings and the incessant damnable drumming, they were in the right. Even if, like me, you have no clear idea of what a credit-default swap is or what the provisions of the Glass-Steagall Act were, you probably understand in your gut that a bunch of really rich, powerful, well-connected people did something that was illegal or should have been, crashed the world economy, and got away with it, and now the rest of us have to pay for it. And you know that is not right. You also know that no one who’s in power now, or anyone who might possibly gain power in 2012, is going to do anything about it. Neither Obama nor Romney is about to affront their biggest campaign donors with regulation or oversight, much less subject them to the indignities of justice. Voting is starting to feel like about as effective an instrument of political change as drumming. Money’s influence in politics is the problem in this country, the metaproblem that prevents all other problems, and itself, from being solved. Occupy Wall Street was an attempt to circumvent that hopelessly corrupted system, to try something new, something that couldn’t be appeased or bought off, appropriated or compromised.

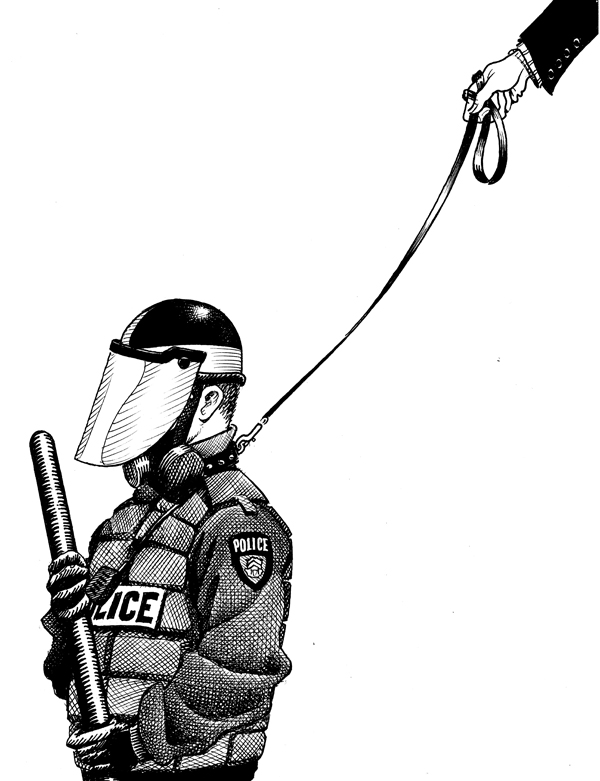

It all ended the way we probably always should have known it would. Mayor Bloomberg, whose legendary obsession with safety and sanitation is evident to anyone strolling through West Harlem or Flatbush, ordered the park cleaned out as though those people and their possessions were so much unsightly litter. It’s a depressing spectacle I’ve already seen too often in my lifetime—the side with uniforms and guns winning yet again. They win every battle. Except I notice they never win the wars. The uniforms and guns have been lined up in a solid phalanx throughout our history against the labor movement, the integrationists, the antiwar protesters—those fearless defenders of the status quo, heroes of Ludlow, Selma, and Kent State. Yet today we have weekends and child labor laws and a black President, and Vietnam and Iraq are acknowledged by all but those most adamantly in denial to have been horrific crimes and blunders. The iron rule of Power and Money is like the law of entropy: absolute and inflexible, its ultimate end the death of everything. Justice is more like life: a fragile, crafty thing that has to resort to ingenious dodges like sex and evolution, memory and books, to circumvent destruction. Maybe it can’t win in the end, but it is also, apparently, ineradicable.

If it’s accomplished nothing else, Occupy Wall Street has at least kicked open the discourse in this country a few more inches. “Economic injustice” is something you’re allowed to say on TV now. The word “oligarchy” has actually appeared in newspaper op-eds. For years the Right could instantly shut this conversation down whenever it arose by bleating “class warfare!” like the class bully telling the teacher he’s being picked on, but this doesn’t seem to be working anymore. Americans have seen the casualties of the financial crisis foreclosed on while its authors got bonuses, they see the health of the economy measured by the Down Jones and NASDAQ instead of jobs or the price of milk, and we’re starting to feel like it only gets called class warfare whenever we try to fight back.

I always liked that old Revolutionary battle flag, DON’T TREAD ON ME, and it irked me when the Tea Party appropriated it as their standard. But we’re all heirs to that revolution, and that flag belongs to all of us. The question in a democracy, the one I would put to the Tea Party now, is: of course you don’t want the government treading on you, but what do you do when you see them treading on someone else--someone you may not agree with, or even like? Stand by and chuckle and applaud the treading? Or do you reluctantly stand up and say, Sorry—‘fraid I can’t let you do that? As of this writing New York’s main tabloids, the Post, which isowned by the 38th wealthiest man in America, and The Daily News, owned by the 147th, are taking the editorial tone of somebody’s laid-off dad after a sixpack, gloating over the beatings of those filthy indolent hippies and celebrating the victory of those traditional old fascist values of tidiness and quiet. Whether their intended audience is buying this line remains to be seen. It’s past time that the Right and the Left both noticed that our traditional nemeses—Big Government and Big Business, respectively—are literally the same people.

The day after I heard that Occupy Wall Street had been forcibly dispersed, I walked down to Zuccotti Park. The space was completely empty except for clusters of cops in riot gear, chatting casually among themselves and avoiding eye contact with anyone else. That whole raucous miniature society had vanished literally overnight, as though it had never existed. I guess we’re all supposed to forget about that silly nonsense now and return to our two remaining officially sanctioned occupations, Work and Shopping. But somehow I don’t think that’s how it’s going to go. Two days after later I went to a massive rally in Foley Square and marched across the Brooklyn Bridge. Anyone whom you asked when they were going to go home, when the Occupation was going to end, invariably answered, adamantly: “Never. Never.” I saw the Occupy Wall Street librarians there, starting over again from scratch with a couple of dozen paperbacks. I still have two slim vooumes in my possession— Paul Harding’s Tinkers and selections from Montaigne’s essays—that bear the circular red sticker marked “OWSL.” They’re like artifacts from a dream that you find in your hand on waking, evidence to hold onto like relics to remind yourself that it wasn’t just a dream, no matter what anyone tells you--it all really happened.