.gif)

This Week You Get an Essay. What do you think of that?

One of the more tactful signs I saw in the Egyptian protests read, "We Appreciate What You Did, But Please Leave." You have to admire their approach; maybe Mubarak will respond to a little politeness, a pat on the back. It reminds me of some of the signs a friend of mine and I saw (and some we laughingly imagined) protesting the Iraq War: “They Probably Don’t Have Nuclear Weapons.”

Over the last few week I've been remembering all those antiwar marches and rallies in 2002 and 2003, and all my fellow demonstrators who thought invading Iraq might be a bad idea. Of course we weren't personally risking as much as the Egyptians are—our most realistic fear was spending a few days under unlawful arrest. And although our movement was a lot larger than domestic TV coverage made it look—our crowds flooded the streets of New York and completely encircled the White House--it was never the kind of truly massive popular uprising we’re seeing in Cairo and Alexandria. And, of course, we failed. In the end gullibility and fear won the day. Whereasin Egypt it started to look dizzyingly possible that underdog pedestrian virtues like reasonableness and decency might triumph for once. I feel a wistful solidarity with those protesters, and wish I could be there standing alongside them.

I find myself thinking of Rebecca Solnit's book A Paradise Built in Hell, about the temporary, jerry-rigged utopias people create at times when civil government fails—the ones Solnit writes about form in the aftermath of disasters, but the same sort of thing happens in times of revolution. For the moment, in Cairo, all the usual worries about work and money and providing for your family--the very worries that usually prevent people from getting involved in politics--are suspended. People feed each other, sleep outside, protect their own homes and stores, look out for their neighbors and bond with strangers. It is inspiring to see human beings behaving so well. And it’s exhilarating to realize yet again that even the most thuggish police states are brittle, flimsy things, founded on fear, and that when the fear evaporates from beneath them they collapse. The underlying political principle is best expressed by an old B. Kliban cartoon:

I’m also fascinated by, and admire, the relationship between the Egyptian people and its army—the passionate respect of the people for its army, the loyalty of the army to the people--so unlike our own rote obeisance to Supporting the Troops by purchasing magnetic ribbons. Universal conscription means the army is an extension of the people, everybody’s sons. Having had an all-volunteer army for decades has alienated our citizenry from its armed forces. The Egyptian army's simple human gesture of declining to commit atrocities is more moving to me than it ought to be--after all, shouldn't we expect an army not to kill the people it's supposed to protect? I can’t help but wonder whether, if such a thing ever happened in America, our army would refuse to fire on its own people. “Our people” seems like a quaint and nebulous notion in the U.S. these days. I worry they’d be able to obey their orders with a clear conscience because they'd know that the protesters were not real Americans but outside agitators and subversives--atheists, anarchists, immigrants, terrorists. I keep thinking of Kent State.

My own government, per what seems to be its official policy, is shaming me by betraying the ideals it professes. At first it reflexively supported its loyal tyrant, sided less equivocally with the populace when their victory began to seem unavoidable, and more recently supports Mubarak's toady now that it's staring to look like his regime might be able to stay in power. It’s all so blatantly craven and calculating. I have to ask, naïvely utopian though it must sound, whether our geopolitical interests might not have been best served in this instance by doing what was obviously right. What’s so ‘real’ about realpolitik, anyway? --I notice it never seems to work out very well in real life. It does not exactly make me proud to be an American to see photos of tear gas canisters labeled “MADE IN U.S.A.” (It’s nice to know we still manufacture something in this country, I suppose. Do we write that on nuclear warheads, too?) I wish there were some way for me, as an American citizen, to make known to the people of Egypt that I stand not with Mubarak or his police or the U.S. but with them, the crowds in Tahrir Square, chanting en masse, sacked out on the grass, laughing together, booing the President on TV, making gutsy runs for more food and water, waiting to see what history does this time.

I know my wish to be there is small and selfish and misplaced--it's not my revolution, or my country, and I wouldn't really belong. But in another sense, it is my revolution, and they are my people. Watching events unfold on Al Jazeera English, I am filled with crazy unpatriotic hopes, hopes indifferent to my nation’s official interests--that a wave of peaceful revolutions will sweep through the Middle East, overthrowing our autocratic allies, that someday our generous creditors the Chinese might replace their own loathsome rulers. Even the Israelis, who have the most to worry about from an unknown new regime in Egypt, can’t help but look on with hope and admiration. At times like these it seems that there are and always have been only two nations on earth: the people marching peaceably in the streets demanding Freedom and Democracy, and the others standing there insisting on Stability and Security, with their guns pointed. I know where I belong.

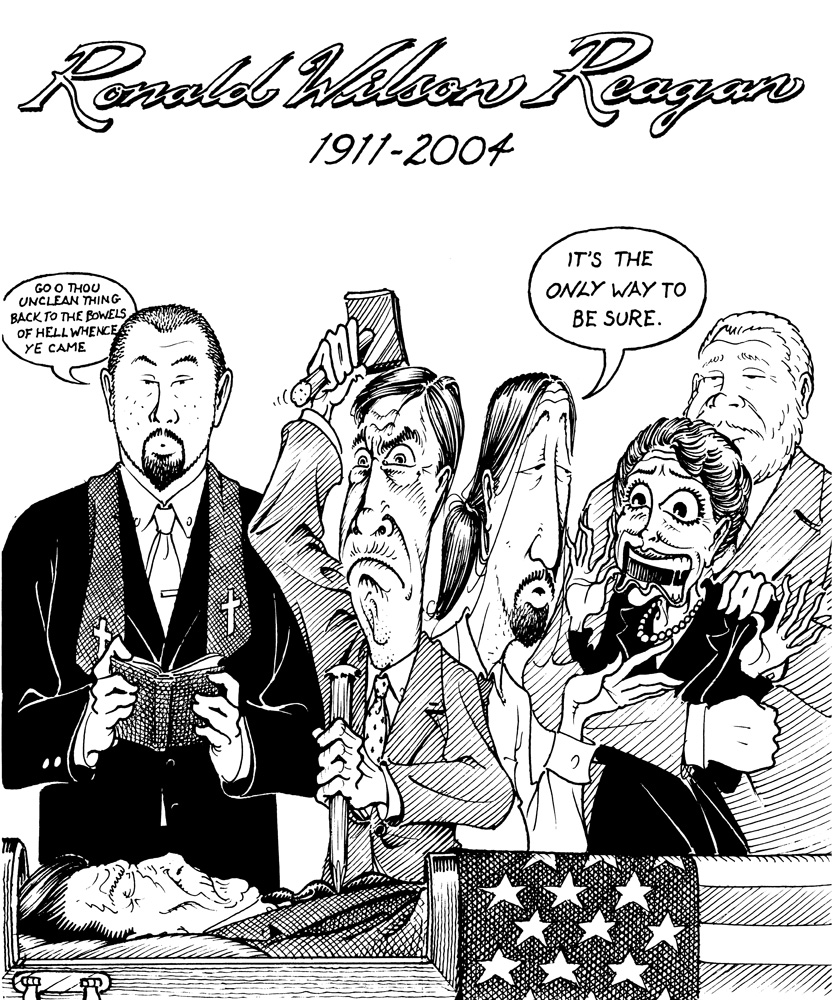

Bonus Cartoon

(in memoriam)

For my thoughts on the Ronald Reagan see my now-classic artist's statement to this cartoon, originally posted June 9, 2004.